Me, Myself, and AI

When does AI learn the secret sauce?

I’m wary of AI. And I believe anyone who is not wary has already outsourced the majority of their brain’s computation to the insidious operator. I’m joking—sort of. I acknowledge AI as an expediter of human progress, and also acknowledge its devastating impacts on our planet and our minds. I—and most humans—are unprepared to litigate the net value of its introduction; and besides, it might already be too late for that. The AI revolution has thus far shown itself to be not a revolution at all, but induction by osmosis. Whatever happened to an opt-in? I digress.

The technicalities of AI and what its proliferation means fascinate me. But the philosophical questions it poses fascinate me more. The primary ones being:

What does it mean to be human?

And does humanness matter?

A recent personal experience with AI confounded me.

Some context: I’m currently seeking some improved income security. Which means I’m in networking mode, reaching out to potential clients and employers, hoping to get a sturdy foothold in the creative space. Blah, blah, blah, you’re bored already. The job search is boring. It’s evolved into a digital wasteland so crowded that it’s barren. I’ve found AI helpful in the following ways: as advanced google search to seek out more niche resources simple queries won’t reveal; as a sanity check on whether my self-marketing might attract the actual roles and clients I’m seeking; and once, to edit something I wrote.1 It’s the editing instance that most struck me.

I came across a job application with the following addendum to its most open-ended question: “(stay short!)” How am I supposed to show them all the ways my unconventional professional background makes me perfect for them while staying short? (Fitting a square peg into a round hole takes a lot of words, didn’t you know?)

Anyway, I worked my ass off on this application. I brainstormed creative ideas to drive the business forward, I beautifully tied my experiences and skillset to the role they described. Every idea and thought was my own. I finished and was proud of it. It was good. I was rereading it before sending it in, and couldn’t move past the few clunky instances where I’d struggled to tie concepts together succinctly and professionally. I couldn’t get past the hurdles of my own voice.

While I’d prefer to sleep on something I’ve written and revisit it, I didn’t want to lose the job opportunity and wanted to get the application out as soon as possible. I had the genius idea to send my answers to ChatGPT to render my writing a little bit more concise, while maintaining all essential information. I was curious if it could help my editing process. Give me a counter point of view, I mused, why not?2

I looked at what ChatGPT sent back. With a minor edit here and there, ChatGPT ironed out those sharp turns in my writing. I hate to say goodbye to words, but when I saw the efficacy of what ChatGPT sent back, I bid farewell to preciousness and hello to staying short. Thanks for the editing help, champ! ChatGPT’s interpretation was more honed, streamlined, efficient, and professional. I sent it in.

Two days later though, it was still niggling at my mind. So I reread my submission. And reread the original I’d written. With some sleep and perspective on my side, I was…. devastated. I’d been looking to tweak a few little problems in my writing, and when I read GPT’s edit, it had! But it was like going to a chiropractor, then realizing in the parking lot that in order to fix my back, they extracted my heart. In the updated application, something essential was missing. There was no spark, no quirk, no me.

ChatGPT’s edits had streamlined my answers, turning my outstretched hand into a compact fist. And silly me, I assumed that meant my words could now pack a punch. Looking at ChatGPT’s edits, I saw that there was no more correct way to phrase my thoughts. But I also saw that the less correct way was better because that version (my version) left the reader with an impression. There’s no one distinct element I can point to as the lifeblood of my answers. In a vacuum, each small ChatGPT edit is great. But in totality, the effect is hollow. Even though what was essential remained, I don’t think anyone reading my application learned anything about me. Maybe that’s why I haven’t gotten a call back… With a thoughtless AI query, I’d eradicated the thoughtful work I was trying to protect. Toss another human work product onto the continuous horizon of sterile, digital noise.

I had asked ChatGPT to make my writing more concise. It delivered. If I’d asked it to make it more flowery, elevated, erudite, it could have. But even that would resulted in a vacant mimic. What concerned me most in this experience was that I asked ChatGPT to edit my work in the first place. I’d given into temptation and fallen for the propaganda: AI is coming; hop on or fall back. I was now a user. And it didn’t feel good.

AI will take human jobs. That’s widely accepted. So what’s the advice? Learn AI, become proficient, employ it. Invite it in. Why? So we can become a second-rate computers? In a world dominated by first-rate computers? If our only way to stay relevant in the face of an AI takeover, is to leverage it, then humanity as we know it is done for. Because success to us already means the kind of precision and speed that only a computer can bring. We already prioritize AI’s strengths and essentialness over our own.

I’m not advocating that we boycott all forms of AI integration. Even now, it’s impossible to use an internet or a smartphone and do so. But I’d recommend slowing down, and considering:

Is efficiency or autonomy more important? (There can be a scale here, I’m only human)

What is self-sufficiency and its purpose? Its role in success?

Empathy? (Computers don’t have empathy. Never forget this.)

If everything is an easy AI prompt away, what is the value of work? And what is worth working for?

I’m curious about humanity’s future. It’s heading for its biggest identity crisis. All of human success has hinged on our ability to accumulate and apply knowledge. When we strip that away, what’s left?

I googled “What does it mean to be a human being?” and Google’s AI summary—something that I did not opt into and that I loathe and read in equal measure— took up the entirety of the results page. The summary said, “a man, woman, or child of the species Homo sapiens, distinguished from other animals by superior mental development, power of articulate speech, and upright stance.”3

Until now, anyone attempting to distinguish humanity has differentiated humans from other animals. Humans are animals with stronger brains, the power of advanced articulation, and physical dexterity. This has implications for how we think about ourselves in comparison to other animals, and how we might define ourselves in the AI era.

Human-Animal:

If we are a species with superior mental prowess, advanced communication techniques, and improved physical dexterity, shouldn’t that mean we are more effective at delivering what every species does?

The AI overview of Google explains: “The primary purpose of an animal species is to survive, reproduce, and pass on its genetic information to the next generation. This ensures the continuation of the species and the preservation of its unique traits.”4

Most animals—even solitary species—function in some way to further their species. (And it should be noted that on today’s overcrowded planet, solitary species often rely on conservation efforts to maintain their existence—perhaps something to consider for humans.)

Humans are not solitary species. Early humans, according to Google’s AI summary, “demonstrated a remarkable capacity for collective care and cooperation. Their survival depended on strong social bonds and mutual support.”5 It is notable that this summary emphasizes the importance of altruism in the success of these early humans: “In essence, early humans' capacity for care and cooperation, evidenced through food sharing, communal childcare, caring for the sick, and altruistic behaviors, laid the foundation for the development of complex human societies.”6

Evolution isn’t linear, and perhaps on our overpopulated planet, there is some evolutionary benefit to increased natural selection. But we’ve spent 95% of our evolutionary history as hunter-gatherers,7 and this collective spirit remains true in today’s chimps, with whom we share 98% of our DNA.8 If these collective elements of our evolutionary history don’t apply, we’ve created a world whose advancement outpaces our evolution, a world where humanity as we know it is an endangered species.

If we’re more advanced than animals and early humans, then we should have improved skills and tactics to continue the species and preserve its unique traits—even if our mechanisms for doing so are different. Shouldn’t progress be channeled to this end? To better deliver these elements and ensure our species’ survival by fostering the very skills that enable our advancement (our brains)?

If altruism is essential to humanity’s survival, how are we working to foster that unique trait?

Is AI good for humanity as a species?

If not, what is its purpose?

Human-AI:

The definition of human does not distinguish between human and computer. And of course, humans aren’t computers, so perhaps it would be redundant. But will there be a point where our definition has to differentiate human intelligence from artificial intelligence?

Our understanding of human assumes that knowledge, mental development, and communication spring from sentience; it assumes that we are the superior thinkers. AI can’t think. But it can erase our need (and ability) to do so.9 Is sentience essential? Is pure knowledge a viable proxy?

AI has no je ne sais quoi. Its directness and its emphasis on efficiency and productivity is hardwired. You have to set the parameters, build a logical case, and ask it to execute something specific. The more specific your ask, the more accurate the output. Every action is to an end. AI is bound by logic. It is concept-driven. AI doesn’t meander. Meandering must be something distinctly human.

The secret sauce—what it means to be human:

A definition of humanity that relies on sentience no longer applies. Whether we believe computers are sentient or not, AI is the first tool that allows us to leverage mental capacity that outpaces our own. AI is an active actor in our society. So, perhaps we’ve rendered sentience irrelevant.

Perhaps what makes humanity distinct is our ability to override our hardwiring (instinctual or programmed). As humans, we’re able to deviate from logic. We can act outside of our best interest with no short-term consequences. Perhaps what makes a human is our ability to act outside of our best interest, and to induce the collective to do the same.

Much of what we deem “progress” socially isolates humans and atrophies our brains. It puts humans at risk, instead of empowering humans to capitalize on what makes them special. We have chosen this rapid technological advancement to what end? So that the world we occupy is no longer the world we were built for? So we can outpace evolution and operate as neanderthals in a technological pinball machine?

We’re so quick to throw away process. But you know what’s process? Living. The more analog my activity, the happier I am. My brain craves satisfaction, not stimulation.

Where do we go from here?

I’m not sure. But we have to put our advanced thinking capabilities to good use, and understand how to differentiate ourselves from our computer competitors. And this means exploring what world we seek to build. AI’s supremacy feels fated, but we have more power to shape the future than we think.

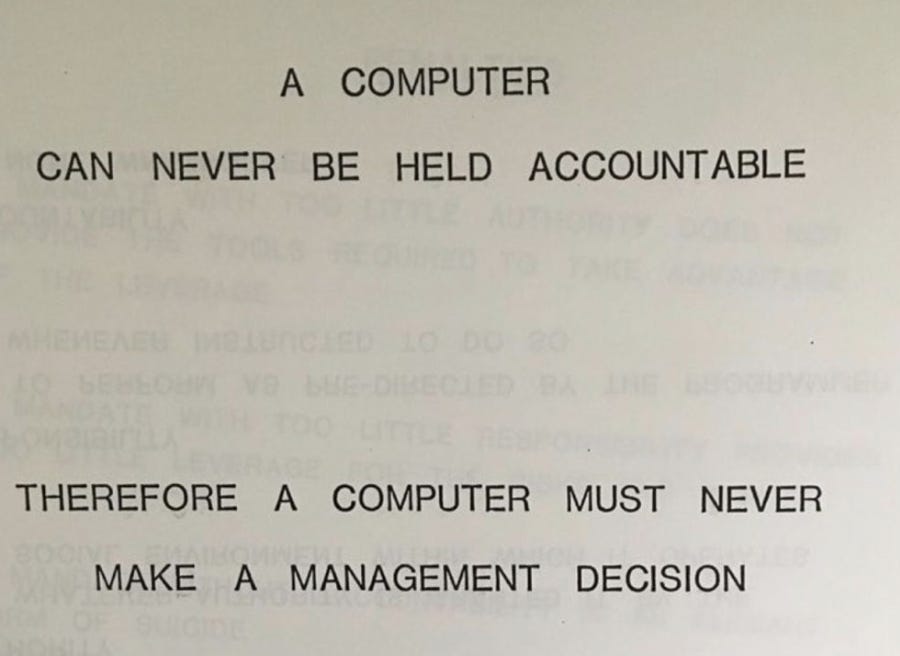

The photo from a 1979 IBM presentation about computers has circulated the internet. Unfortunately, the presentation was not memorialized in the IBM archives, so the remainder of the presentation is lost to history. That hasn’t stopped some inventive internet users from manipulating the image to see what words lie beneath this capture. One such investigator10 found:

THE COMPUTER MANDATE

AUTHORITY: WHATEVER AUTHORITY IS GRANTED IT BY THE SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT WITHIN WHICH IT OPERATES.

RESPONSIBILITY: TO PERFORM AS PRE-DIRECTED BY THE PROGRAMMER WHENEVER INSTRUCTED TO DO SO

ACCOUNTABILITY: NONE WHATSOEVER.

AI is executing on behalf of humans. Any authority AI has right now is human-given, granted by us and our social environment.

If we flip the script, AI—and its trajectory—will respond to it.

If we continue to accept an exclusively for-profit society, then efficiency and maximum knowledge accumulation will win out. Money comes at the cost of humanity—every single time.

And what does technology cost us? AI might save lives in the short-term, but does it render the living it enables less-alive? What does it do for humans in the long-term? How can we leverage AI to amplify humanity, rather than mute it?

How do we maintain our value as a species?

A case for empathy: Though we live in a threatening world, we are disconnected from the threats facing early humans. Altruism doesn’t necessarily stem from empathy, but empathy might be the surest way to motivate yourself altruistically. Get a coffee somewhere new. Read a book by an author whose name you can’t pronounce (actually, read any fiction book— it promotes empathy). Spend time outside. When you’re speaking to someone, ask them questions and listen to the answers. Tune in to your surroundings.

A case for the inefficient: With our high processing power and animal roots, humanity has a unique ability to deviate from a direct path. We have the ability to get distracted, to take the long way, or to take an unexpected route. This alone gives us cleverness and ingenuity—two features, that as of yet, computers don’t have. Take a long walk with no headphones, and turn down streets you’ve never walked down before. Spend some time without a plan. Be bored. Be quiet. Your brain will speak up.

Perhaps our uniquely human seductive power is preciousness. Perhaps that is the only way to make a noise anyone can hear.

—————————————————————————————————

Notes:

I say none of this as a purist. While simple human problem solving leads to satisfaction, so does a happy marriage. And I met my husband—who was living across the country at the time—on a digital dating app. So many things I love about my life wouldn’t exist without this human technological sprint. There is no black and white. But it’s worth exploring the gray: as a species, are we better off? How do we decide what technology is valuable and which is not—and does our species’ embrace of “progress” preclude us from making that choice and opting in intentionally?

* For the record, I’ve always loved an em dash and I always will. Every em dash in this essay was added by my own hand. Apart from the Google AI summary results I quoted, this piece was written without AI.

It should be noted here that ChatGPT is an LLM and should not be used for advice or accuracy (basically, to use it as a self-check can be redundant). It basically tells you what you want to hear. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman warned ChatGPT users against trusting AI. ChatGPT “hallucinates” and misrepresents inaccuracies as fact—and when communicated to us via human language, it feels a lot like lying. Substack author, Amanda Guinzburg, recorded her haunting experience with ChatGPT’s misleading inaccuracies—and its apologies (remember, language model, not brain) when Guinzburg fact-checked it.

Is there something inherently wrong in doing this? Our society isn’t sure.

Yes, I understand the irony of quoting an AI summary in a piece concerned about the impact of AI. And I do not mean to ignore the underlying human research and work that makes these summaries possible. In this piece, I’m quoting the Google AI summary demonstratively as the best proxy for collective human understanding of a topic. This feels relevant as I explore these concepts through the lens of universal truths, and aspire to engender thought in the average person (who increasingly, relies on AI’s point of view as a proxy for their own).

Hypocrisy being a distinctly human trait, I’m using AI summary to define things I consider to be universally accepted truths.

Same note as before—using AI summary to define things I consider to be universally accepted truths.

Continued AI summary: “Here's how they cared for the collective:

Sharing Resources: Early humans recognized the importance of sharing vital resources like food, especially successful hunting kills. Sharing helped ensure the survival of the group, strengthening social bonds in the process. Archaeological evidence suggests that early humans transported tools and food over long distances to bring them back to communal gathering places, indicating a practice of sharing resources.

Communal Childcare (Alloparenting): Hunter-gatherer societies often relied on "alloparents", or non-parental caregivers, to care for infants. This provided infants with consistent care and support, according to New Atlas potentially reducing stress on mothers and benefiting the child's development.

Care for the Sick and Injured: Archaeological evidence suggests that early humans, including Neanderthals, cared for sick and injured individuals who would have struggled to survive alone. Evidence of individuals surviving for extended periods with severe disabilities indicates that they received support and care from their social groups.

Cooperative Breeding and Altruism: The "cooperative breeding hypothesis" proposes that humans evolved a tendency towards altruism and cooperation by caring for infants not just by mothers, but by a wider network of individuals. This cooperative approach to raising children may have contributed to the development of complex social structures and language.

Mutualistic Collaboration: The "Interdependence Hypothesis" suggests that early humans created ways of life where collaborating with others was essential for survival, leading naturally to altruistic behavior as individuals relied on their partners for foraging success.

Social Networks: Expanding social networks enabled humans to interact and exchange resources with groups located far from their own, which further enhanced their ability to survive.”

Big History Project: Chapter 4: Humans

There is no definitive study on AI use on the brain; but computer scientist Nataliya Kosmyna at the MIT Media LabA recently published an early, not yet peer reviewed study showing potential for AI damaging critical thinking skills. However, speaking from personal experience, completing something with AI’s help feels like being handed an ice cream cone when you’re really, really hungry.

Mastodon wser: @mhoye@mastodon.social in this interesting thread on the 1979 IBM presentation